JUST how far, and how fast, Australia has come in meat processing has been documented by Stephen Martyn in his book, World on a Plate.

The book was a seven-year labour of love for Mr Martyn, who has a deep history in the sector. He is currently the national director, processing, of the Australian Meat Industry Council (AMIC).

FarmOnline is publishing extracts from the book.

Beef or whale? Only at Byron Bay

THE meatworks at Byron Bay has a special place in history, not just for its valuable real estate of six acres beside the main beach of the famous northern NSW town, but also for its association with the whaling industry.

Known as the home of the rich and famous and an established holiday destination, in 1912 the Byron Bay Co-operative Canning and Freezing Company Limited was established at the southern end of the town's main beach. The plant was running just three months later at a cost of £4500 - a significant blowout from the tender price of £3050.

The war years guaranteed a market for its product, but despite a shortage of livestock in the early years, it had 100 hands processing around 100 head daily by 1919. It closed later that year and languished until sold to Norco in 1927 and was then leased to the export meat processor AW Anderson.

Anderson installed new machinery, refrigeration and a freezer and promoted the plant widely to attract livestock for processing and transport to the Sydney Wholesale Markets.

Its reopening in June 1930 was seen as a vote of confidence in Byron Bay in the dark days of the Depression. Anderson's later gained access to the UK, and then the US in the 1960s, when it again rebuilt the plant at a cost of over $500,000.

Anderson eventually sold the works to FJ Walker in 1968. FJ Walker was taken over by Elders IXL in 1983 and they closed the plant amid the ensuing rationalisation with the loss of 360 jobs. The plant had been marginal for years, but the closure caused genuine hardship for employees with few employment alternatives.

The national TV show Countrywide flew in a crew for a documentary on the basis that the plant's closure was the scapegoat of Elders IXL corporate errors, but it generated little sympathy. Many local residents were happy to see the plant and its smell leave the beach.

Byron Bay Whaling Company

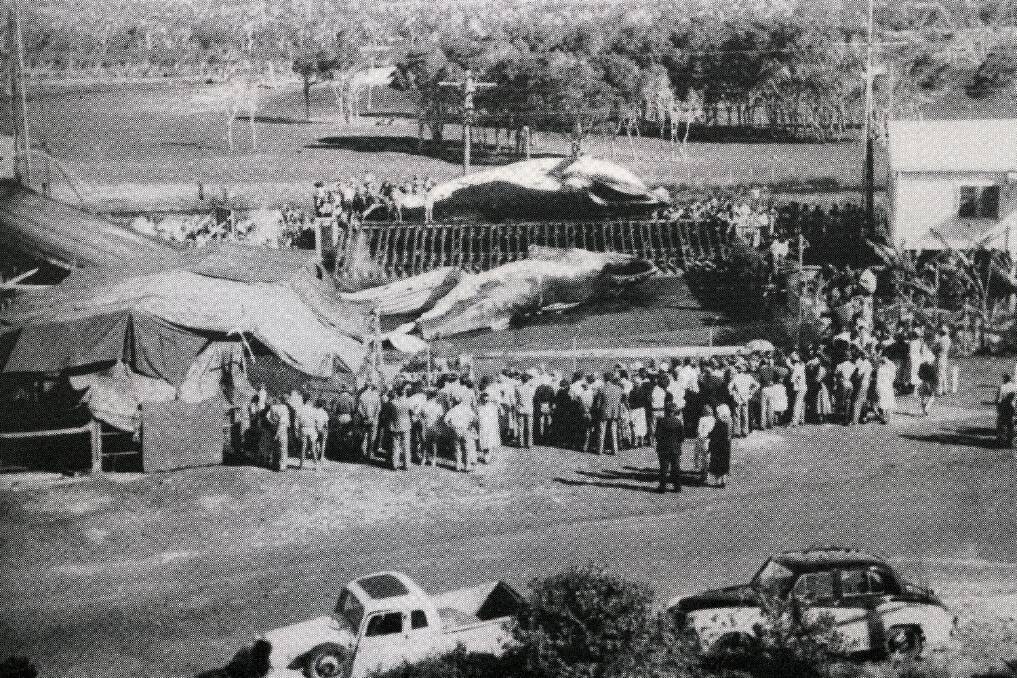

Anderson also formed the Byron Bay Whaling Company in 1954, right next door to the meat plant. Australia had been a signatory to the 1946 International Whaling Convention. The government was keen to restart this old industry and granted the Byron Bay Whaling Company a quota of 120 humpback whales a year, which rose to 150 in 1959.

Most of the whale meat became pet food (packed into trays, snap frozen and exported to England) but a small amount was sold to North Coast fishers for their traps. Some of the meat and the bones were rendered with the blubber.

When the oil was decanted off (up to 10 tonnes from a large whale) the solids were dried to become meat meal and the liquid went into stock feed. Whalebone, or baleen, had value in fashion until the wide use of plastics in the 1960s.

Stan Nolan was the primary industry meat inspector at the Anderson’s meat plant on the beach in 1954 – and he became the whaling inspector when asked by the fisheries department to 'stroll next door' if a whale was shot. He undertook both tasks until the whaling company closed in 1962.

His duties included reporting on any females in calf, as these were protected, and the collection of 'whale marks' used by the English, Russians and Japanese to track whales. There was a reward for their return.

Once the season started (around May) the factory worked 24 hours, seven days a week on two 12-hour shifts – ie. 84 hours per week (40 hours on normal pay and 30 hours on double time) – better than staff could get at the meatworks.

Brian Andrews worked at the plant for a time in the 1960s and recalls some disadvantages.

"Situated on the most easterly point of Australia it only had a 180-degree livestock procurement area," he recalled. "Being a great fishing area, every time the fish came on, half the employees went fishing".

"Effluent from the plant was pumped directly into the ocean and one employee’s job had been to sit on the whaling station wharf with a .303 rifle and shoot the sharks.

"This was the same wharf where we used to jump into the sea and surf back to shore! The burley attracted many sharks, but for locals it meant that the northern end of the beach was quite safe - all the sharks were at the other end!"

When Anderson's went in to receivership in 1967, the receiver tasked Jack Ware to get the plant running cost effectively or it would close.

Jack remembered: "I noticed on my second day that all the staff had gone to a meeting in one of the halls, so I decided to put my new no-frills management style into practice and marched in, telling them that if they weren’t back to work in 10 minutes they would all be looking for a new job".

"Within six minutes they started filing out and I was feeling good that the new style was paying dividends. The trouble was that they just kept walking straight past me and out the gate and it took three days to get them back."

An edited extract from World on a Plate: A History of Meat Processing in Australia which is available for purchase online. Photos prepared with special thanks to the Byron Bay Historical Society (Reproduced from Ryan (1984) with kind permission of the author).