The 1980s

The National Farmers Federation stamped itself as one of Australia's most powerful lobby groups during the 1980s by busting union domination of the shearing and meat industries and vigorously attacking the economic and tax policies of the Hawke Government.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

No farm organisation in Australia's rural history had ever enjoyed such great influence over national economic, trade and industrial policy.

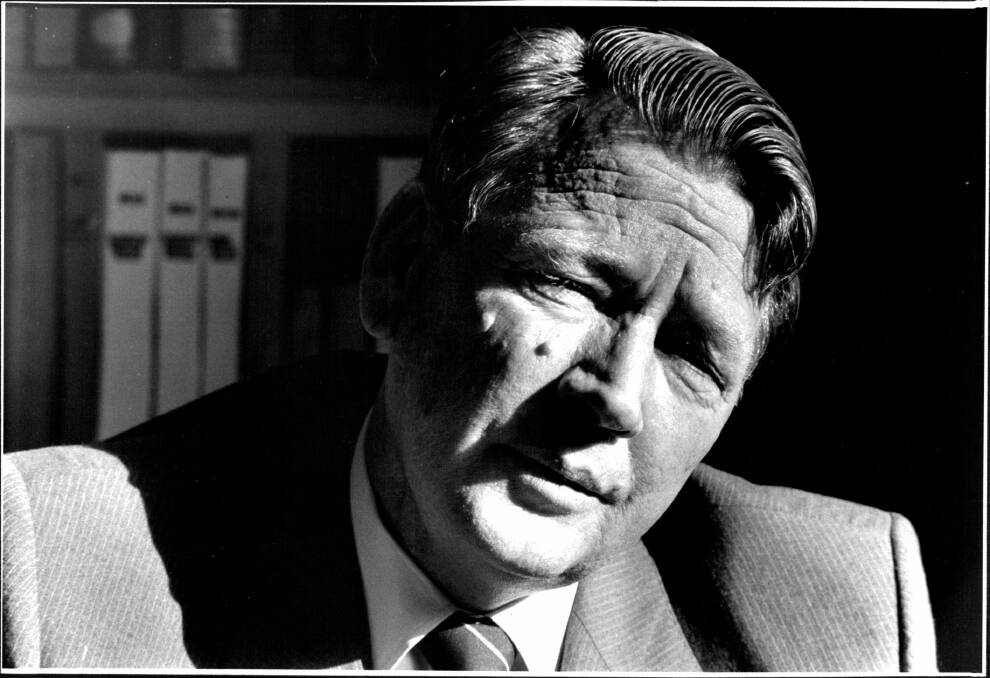

And front and centre during the action-packed decade was Ian McLachlan, a hard-nosed grazier and businessman from South Australia, who first shot to national prominence as a batsman who was picked once in the Test team but played 12th man.

McLachlan returned to the national stage in 1978 when he led farmers in a successful campaign to force unions to lift bans on the export of live sheep from SA.

That victory propelled him towards the fledgling NFF, first as chairman of its affiliate, the Wool Council of Australia, from 1980-84 and then NFF president from 1984-88.

McLachlan believed the union movement had grabbed far too much power thanks to weak business and political leaders.

The NFF's economic and industrial policy manifesto was built around wage flexibility, financial deregulation, trade reform and improved international competitiveness.

It developed a comprehensive agricultural "blueprint" called Farm Focus which was ahead of its time and advocated for major economic reforms including the removal of all industry protection and better government control of inflation.

The NFF quickly emerged as a loud and telling critic of the Hawke-Keating Government's economic and tax policies in the 1980s.

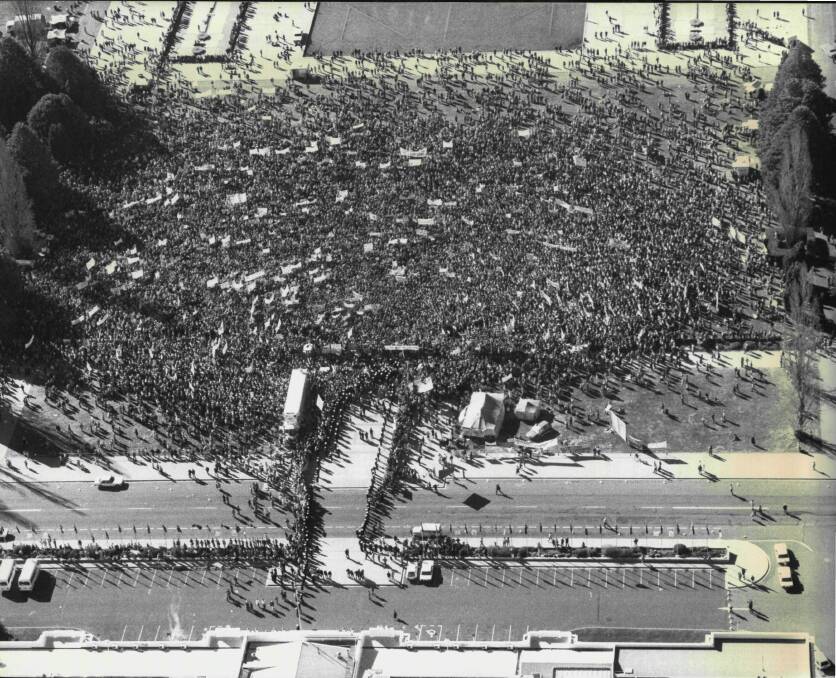

The poor relations between the two reach a peak on July 1, 1985, when 45,000 farmers and their supporters marched on Parliament House to protest against high interest rates and proposed tax and financial reforms, notably capital gains tax and fringe benefits tax. It was the biggest farm protest in Australian history.

The former was seen by the farm sector as a back-door return of death duties and the latter an attack on the perks provided farm workers such as free meat, housing and electricity.

The size of the march sent a clear message to all politicians that the rural community was fed up with Australia's economic mismanagement.

The rally was also significant as the launch date for the NFF's Australian Farmers' Fighting Fund - a pool of money to be used to fight precedent-setting legal cases on behalf of farmers.

NFF was involved in two game-changing industrial battles in the 1980s - the wide combs and Mudginberri abattoir disputes - which broke the power of the unions and paved the way for improved efficiency in shearing sheds and abattoirs.

Wide combs, typically 86 millimetres with 13-teeth, had been banned in Australia by an Arbitration Commission ruling in 1926 at the behest of graziers who wanted to stop shearers widening ("pulling") the teeth of combs which resulted in a faster but shoddier job.

Shearers, backed by the Australian Workers Union, stuck with the narrow 64mm combs for the next 50 years or so but a growing influx of New Zealand shearers working in Western Australia's rapidly expanding sheep industry in the 1960s and 1970s brought wide combs with them.

The AWU had little power in WA where NZ shearers started modifying their wide combs, which ironically were made in Australia, to better suit Merino sheep.

Shearers in the eastern states began to quietly experiment with the wide combs, too, but most were frightened about upsetting the AWU.

All that changed when Blayney district shearing contractor and gun shearer, Robert White, openly used wide combs in a shearing shed at Canomodine Station near Canowindra in April, 1981.

The dispute quickly flared into an ugly four-year struggle with rebel shearing teams bashed, sheds burnt to the ground and properties and their owners black-banned.

The NSW Livestock and Grain Producers Association (now NSW Farmers) asked the NFF to become involved on its behalf. Both could see the economic benefits of wide combs for both growers and shearers.

The McLachlan-led Wool Council of Australia became directly involved in the dispute in October, 1981, warning the AWU it was losing patience and urging the union to agree to trials of wide combs.

Meanwhile, the dispute was the subject of a lengthy investigation and hearing in the Arbitration Commission which came to a head in December, 1982, when Commissioner McKenzie ruled wide combs had a place in the Australian shearing industry.

In March, 1983, the union lost its appeal against his decision which sparked a shearers' strike from March to May.

NFF industrial director at the time, Paul Houlihan, remembers McLachlan had to work hard to convince graziers they could win the fight.

"They hadn't won a stoush against shearers since the 1890s," he said.

Houilihan said plenty of sheep had been shorn during previous shearers' strikes but the newly-shorn sheep were hidden away in back paddocks.

This time McLachlan had to persuade them to not only shear their sheep but run them in roadside paddocks so union shearers could see they were losing income.

Houlihan, who had led the growers' case in a series of lengthy Arbitration Commission hearings, remembers one of his biggest critics was Alec Morrison, head of Rupert Murdoch's Merino empire based at Boonoke stud in the NSW Riverina.

During a meeting with McLachlan, the media baron was told about his manager's criticism of NFF's handling of the dispute and he asked what he should do.

"Tell him to start shearing," was the blunt reply.

He did and Houlihan said that was a big psychological blow to the union as Boonoke was a 16-stand shed.

"We broke the AWU, they virtually haven't got any members in rural Australia today. They forced it on us," he said.

Houlihan said the NFF's success in the wide combs battle provided the confidence and knowledge to take on the meat union in the Mudginberri abattoir dispute.

Like wide combs, Mudginberri was about modernising an archaic industrial award which was reducing returns to livestock producers and sending meat processors broke.

"We had to change the meat industry," Houlihan said. Over-staffing was so bad in abattoirs that butchers barely had enough room to move on slaughter chains, he said.

The unlikely battleground to confront the powerful Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union (AMIEU was a small, isolated abattoir in the Kakadu region of the Northern Territory called Mudginberri.

The abattoir, owned by an ex-American Jay Pendarvis, was slaughtering feral buffalo for export.

The plant was operated by contract labour employed outside the industrial award which was fiercely protected by the AMIEU.

Most were itinerant seasonal workers who worked hard but earned big money during the dry season each year.

The AMIEU moved to bring Mudginberri and several other small meat plants in the Top End under the award, fearing major job losses if abattoirs across Australia adopted similar employment practices.

The meat industry was in serious decline at the time with widespread abattoir closures caused, in large part, by steep processing costs caused by the award-controlled "tally system".

The high cost of meat processing was also hurting returns to farmers so NFF got involved in the dispute which ran from 1983-85.

A decision on the award was handed down in April 1985 by Commissioner McKenzie which specified minimum award standards but also included a clause upholding individual non-union contracts

The union established ACTU-endorsed picket lines at Mudginberri in May, 1985, and while the workers ignored them the Commonwealth meat inspectors at the plant refused to cross which stopped production for export at the plant.

The AMIEU was successfully prosecuted under section 45D of the Trade Practices Act (secondary boycott provisions).

Peter Costello, a barrister who later became federal Treasurer and a major industrial reformer in the Howard Government, acted for Pendarvis and the NFF.

Pendarvis was awarded $1.75 million in damages which, along with $144,000 in fines, almost sent the AMIEU broke and dramatically weakened its power.

Towards the end of the decade the NFF and the Australian Conservation Foundation were fundamental in establishing Landcare, a program to promote sustainable agricultural systems and sustainable natural resources.