THE new federal government may be putting a lengthy time frame on calling game over on the live sheep trade but it is standing by its pre-election promise to do just that.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

The consequences for Australia's sheep farmers and rural communities are massive. Before summer month voyages to the northern hemisphere stopped in 2018, revenue earned from the trade was around $100 million a year. Economic analysis commissioned by the sector's research development corporation indicates that nearly half that was retained on farm.

However, the bigger picture is what the ban might mean for many other agriculture sectors.

Are cattle next?

Many in the beef industry, including shadow minister for Northern Australia Susan McDonald, believe there is no doubt that banning sheep exports would open the door to banning live cattle exports.

New Agriculture Minister Murray Watt says his government has 'absolutely' no plans to phase out the live cattle trade.

However, it is certainly the policy of The Greens and in the demand list of the animal rights lobby that pushed so hard in the run-up to the election for the Labor live sheep ban to be put on the record.

The devastation to the cattle industry of a live export ban is well documented. The compensation bill from the 2011 Gillard Government halting of shipments to Indonesia, which has now been ruled illegal by the Federal Court, is still being nutted out but will likely cost the taxpayer in excess of $600 million.

Northern cattle live export leaders say while they've heard the promise not to ban their trade loud and clear, that says little about the temperature of support for the trade.

"Saying you are not going to ban something could be seen as the most passive form of neutral non-support," said NT Livestock Exporters Association chief executive officer Tom Dawkins.

"A government can see an industry thrive or wither on the vine by taking, or not taking, certain steps and actions.

"Our dialogue with Labor is around trying to gauge the strength and nature of its support for our industry.

"We have just had a new round of legislated cost recovery charges added to the cattle trade, and the department is seeking to return to independent observers to the short-haul trade, which can come at a $25000 per-voyage cost.

"So the question is not so much do you promise not to ban the trade but will you let our industry decline through ever-increasing regulatory costs or because of market access uncertainties?

"Will the necessary support be there amid trade access hurdles that may arise due to a lumpy skin or foot and mouth disease outbreak?

"Indonesia is making it clear that affordable protein is a national priority and access to Australian cattle is very much needed - is that a priority for the Australian Government?"

Wider consequences

A ban of live sheep exports would see Australia's reliability as a trade partner take a beating, potentially affecting many more agricultural sectors, analysts and livestock industry leaders have warned.

Kuwait takes the majority of Australia's live sheep, followed by the United Arab Emirates and then Oman.

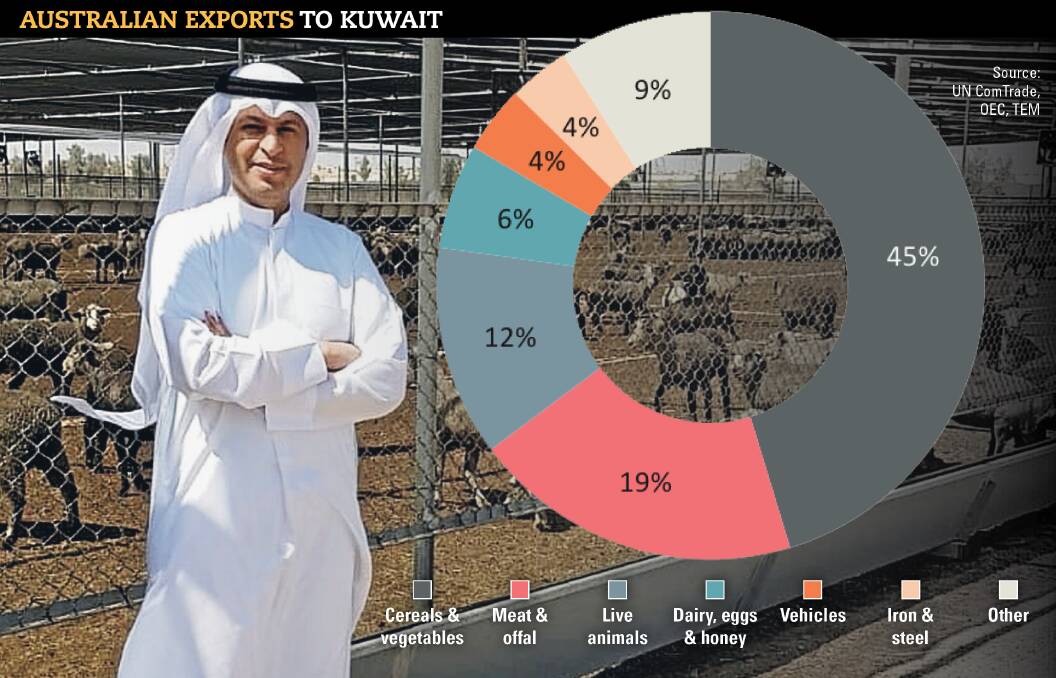

Thomas Elders Markets ran an analysis of export flows to Kuwait, which showed over the past five years nearly $500 million worth had been shipped, with nearly half that cereals and vegetables - primarily wheat.

The UAE are an even larger overall trade partner with Australia, with a total average annual export value of nearly $3 billion.

The TEM work also shows the UAE and Oman provide Australia with a reasonable amount of key agricultural inputs such as petroleum and fertiliser.

TEM's Matt Dalgleish said since the three-month moratorium on Australian live sheep shipments was put in place, Kuwait had been forced to shop elsewhere and the likes of Romania, Africa and Saudi Arabia had stepped in.

"It's not uncommon for negotiations around the boxed product and live animal trade to go hand-in-hand," Mr Dalgleish said.

"There are live-ex competitors who can take our place and they can also supply boxed meat,"

Kuwait's live sheep importers have been very vocal about Australia becoming an unreliable trade partner.

The threat that they will take their business in other commodities, both imports and exports, elsewhere was real, Mr Dalgleish said.

The situation would be mirrored in cattle, he said.

Indonesia is Australia's largest live cattle buyer and also our largest wheat market. And it is our fifth largest boxed meat market.

"Being an unreliable trade partner in any sector is never good and always had wider consequences," Mr Dalgleish said.

"Hopefully careful consideration is given to the importance of the bilateral trade relationships that exist between Australia and Kuwait, UAE and Oman before any final decision is reached to permanently end the live sheep export trade."