THE balance between chasing high farmgate prices and avoiding high input costs has always been the determining factor of whether livestock or grains is the best game but times are changing.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

Agtech, societal demands, lifestyle goals and even a change in the way farmers see themselves are feeding into decisions about whether to plant or breed.

While there has been widespread commentary about people getting out of sheep and cattle, a review of Australian Bureau of Statistics agriculture census data by Meat & Livestock Australia analysts has busted some big myths.

Flock and herd numbers per farm may be falling but the number of farms running sheep and cattle are increasing.

From 2016 to 2021, the number of properties running sheep increased by 703, or 2 per cent, to 31,839. The total number of sheep in Australia also increased by half a million head, MLA reported.

However, the number of sheep held per property fell by 30 head.

In the same period, the number of businesses running cattle grew by 1.6pc, or 736 farms, to 47,757.

However, the number of cattle per enterprise eased by 2pc to 511 head per business.

ALSO SEE:

Manager of market information at MLA Stephen Bignell said those figures run contrary to widespread commentary that the livestock business in Australia was in structural decline.

What is really interesting, however, is that in that same period, there was a 12pc increase in the area of land planted to wheat, despite only a marginal increase in the number of farms growing wheat.

Clearly, people have sought to capitalise on superb growing conditions and ripper grain prices and turned over more of their country to grain production.

Ironically, Mr Bignell said, in some parts long considered die hard wheat belts, sheep numbers are up while some traditional sheep ground has seen big declines in stock numbers.

"What it all shows is you can no longer put farms into separate boxes," Mr Bignell said.

"Farms may not identify as a livestock operation but are running sheep.

"There is better market information today, and people are less likely to be 'absolute' farmers - identifying as just a wool grower for example. They are far more open to chasing returns, reacting to price signals, diversifying and being flexible."

Mixed farming heartland

All this has meant that the traditional mixed enterprise heartlands in Western Australia, Victoria and South Australia are no longer genuinely the king of that space.

MLA's analysis identified there were only five shires in Australia - Forbes, Bendigo, Wagga Wagga, Corowa and Goondiwindi - that truly had equal amounts of agricultural land used for crop production and grazing.

However, there were close to a hundred more that operate within the 40 to 60pc range.

Experienced agriculture consultant Cam Nicholson, Nicon Rural Services in Geelong, Victoria, said shifts between grains and livestock had been occurring for decades and came down to diversification to manage business risk.

Mr Nicholson was involved for many years in the renowned Grains and Grazing program run jointly by the two sector's research and development corporations.

The trade-off between income and costs waxes and wanes, and farmers switch out parts of their country accordingly, he said.

In the south, for example, livestock gross margins have improved 2.5pc on where they were 10 years ago. Meanwhile, crop input costs have risen phenomenally.

"Put the two together and bringing more livestock into the business has made sense in the south," Mr Nicholson said.

Indeed, analysis from Episode3 shows cropping has seen, by far, the biggest hikes in input costs from 1990 to 2020. Cropping costs jumped by more than 300pc, with dairy next at 250pc. Sheep was just 100pc and beef was on a similar trajectory.

Episode3's Andrew Whitelaw listed chemicals and fertiliser as the biggest driver of that, with repairs and maintenance of gear contributing too.

While those cost-return fundamentals have always been going on in the background, there are new dynamics now playing into decisions around grains versus livestock - advances in technology being a big one.

"Grain-growing agtech advanced faster than livestock," Mr Nicholson said.

"Fundamentally, with bigger equipment came bigger paddocks and greater efficiencies but that also reduced the ease with which people could swing back into livestock - fences literally came down.

"Yet now, the tech game in livestock has started to improve making that job easier."

Not only is it offsetting the labour issue in livestock but it is allowing significant improvement to herd performance because individual animals that aren't performing can be identified and culled far more easily.

Mr Nicholson believes the fluctuations between grains and grazing will continue.

Mostly, farmers seem to want to keep a finger in each pie. Complete shifts out of one tend to only happen with changes in generation, he said.

Longest hours

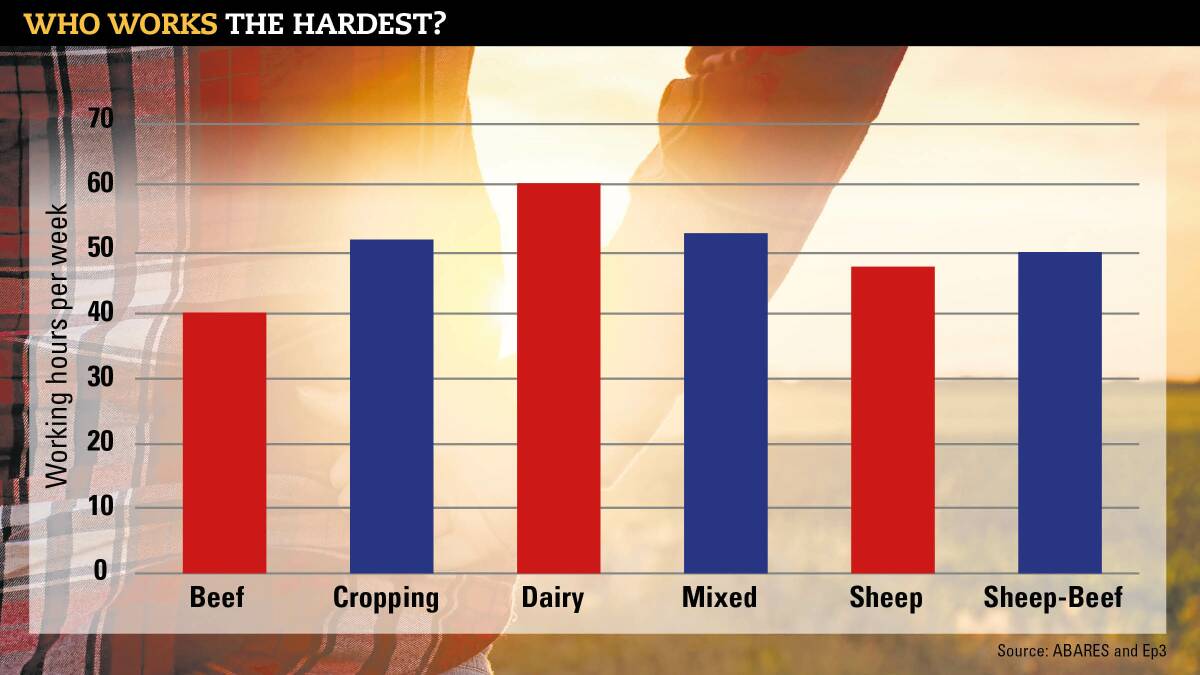

Of course, there is also the question of which job is the hardest.

Mr Whitelaw has also just published entertaining analysis of Australian Bureau of Agriculture Resource Economics data around hours worked on farms.

Dairy farmers put in the longest days at an average of 61.2 hours a week.

Beefies have the shortest week at just 40.4 hours. Grain growers nudged the 50 hour mark.

Mr Whitelaw claimed ag market consultants typically work 27 hours a day, on par with ag journalists.